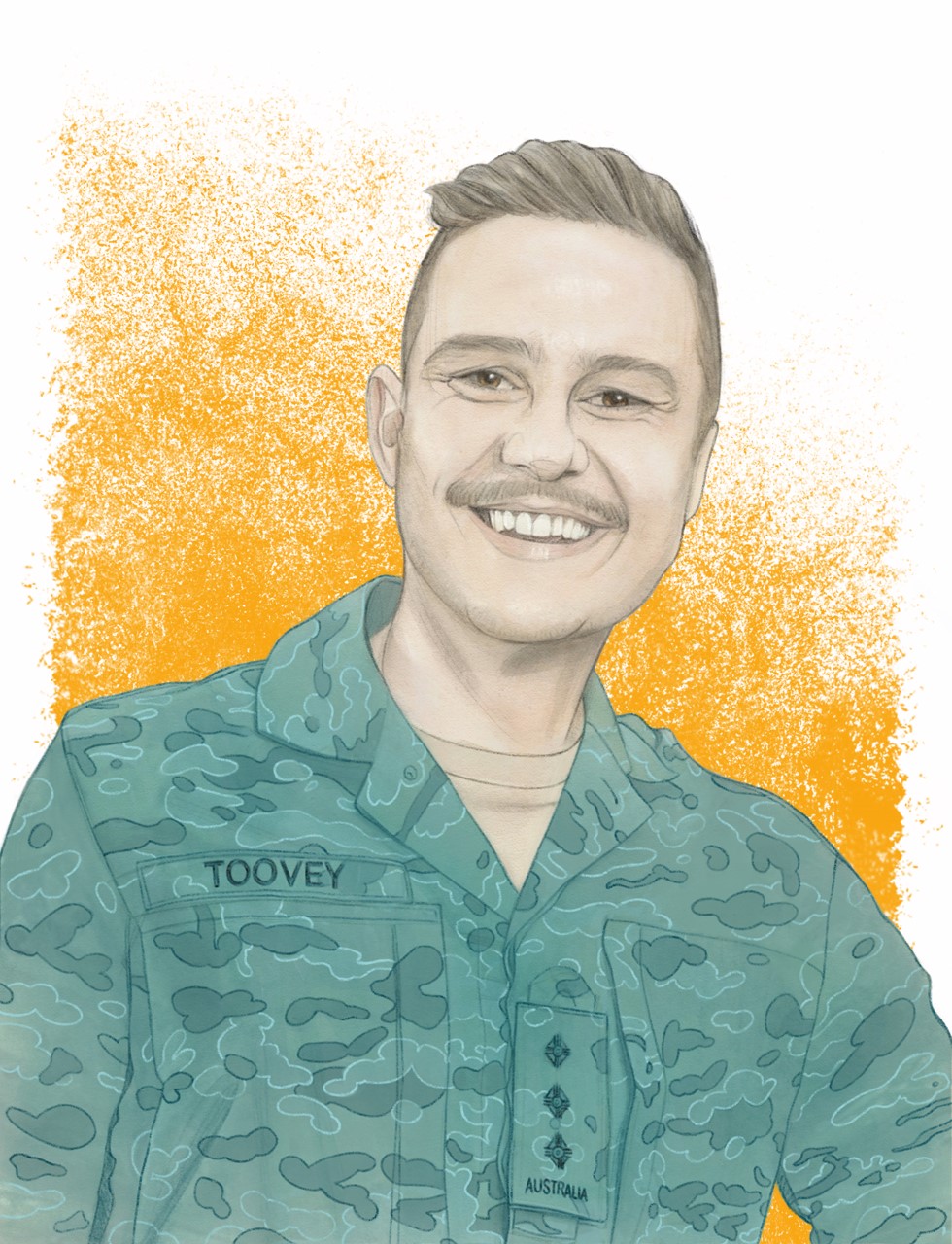

I was four years into my Army career, I was 21, and at that stage I was fit and healthy. I’d had no real experiences with cancer at all — it was pretty foreign to me. It was just from what I'd seen on the news and movies.

I noticed an obvious lump on my right testicle, but I couldn't pinpoint the day to go, "Oh, there it is," I just knew it was there for a while. I Googled ‘lump on testicle’ but everything comes up, from you've got a cyst, you've got testicular torsion, you've got testicular cancer, you've got six months to live. Then naturally I looked at that and went, "Oh, well it’s probably just a cyst. I'm probably overreacting here. I'm sure it's nothing." Deep down you just want to believe that yourself. But eventually it went on enough for me to kind of say, "Yeah, that’s not likely.”

The turning point — I remember the date well because it was my dad's birthday. I was in my Army room, lying on my bed, wishing my dad a happy birthday on the phone, and I said to him, "I've got this lump on my testicle." I was 21, I was still a bit vulnerable talking about that stuff. He simply said, "Why don't you just go off to a doctor, mate, and get it looked at? Better safe than sorry." It was the prompt I needed to say, "Actually, why don't I just go a doctor, it's not that hard?”

The assessment was a bit uncomfortable, but at the same time, a lot easier than I thought. You build it up in your head to be this whole big thing. He just felt the lump, felt around, checked all my other vital signs like doctors do. I vividly remember he said, "Look, mate, it's probably nothing. It's probably just a benign cyst, which can be quite common in the testicles, but we'll still send you off for an ultrasound. We'll get you an appointment this afternoon just in case it's something a bit more serious."

It wasn’t until I had the ultrasound, when I saw the person giving it and saw it on the screen — that's when I thought, "hang on a second." I thought I could just tell from her face. I remember asking her, "Is that normal? What's that? Is that one of those..." She was pretty silent and kept saying, "Oh, look, the doctor will go through it with you." At that point, I felt a fair bit of anxiety.

Looking back on the moment I was diagnosed, I was still pretty naïve and a bit ignorant to what that actually meant. I didn’t have had a clue about the next steps and the chance of it spreading, or any of those things. I don't think it was until I processed it and called my parents and really looked into what it actually means when you've just been told you've got cancer as a 21-year-old, and that's when I got pretty emotional.

For a lot of people with testicular cancer the only treatment they ever need is removal of the testicle. Happy days, a bit of surveillance every three to six months for the next couple of years, and they go on to live a long, happy, and healthy life. To me, that reinforces the importance of getting it early, which I had to learn the hard way because by putting it off, it already had time to spread up to my abdominal lymph nodes and started to spread further, as the follow-up scans eventually showed.

I realised it was more serious as soon as I started hearing things like chemotherapy and meeting with an oncologist. Realising I'm going to lose all my hair, I’m going to feel unwell, and they're not sure how it's going to impact my Army career. That’s when the frustration came into it. I had laid on my bed multiple times feeling this little lump, putting it off, cracking on with my day, and I did that for months.

Had I just wandered across to the doctor earlier who knows where I would be. There's a very high chance it would have been caught before it spread. I wouldn't have had that initial surgery, those months and years of recovery and treatments, added stresses and pressure, potential damage to my body. God knows what could've been avoided had I just gone to the doctor a couple of months before I did. But from there I didn't have much of a choice — I just had to crack onto it and forget about all that.

In the early days of chemotherapy where I was struggling in hospital (I would've been 22 at that stage), I'd go to the bathroom and catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror and I looked like a different person. While my Army mates were posted around Australia, living out their careers, I was stuck walking around in a hospital for my daily exercise. I was unwell, hooked up to chemo for eight hours a day, having these toxic drugs put into my body, so there was a time I do remember feeling down and unhappy with where I was. But I put a lot of trust in the doctors and they'd constantly reassure me that I had one of the better cancers to get as far as survivability goes, and they were confident the chemo would do its job.

Unfortunately, I fell into that statistic of needing further treatment and I had to have a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection — a major open-abdominal surgery. I spent the next 12 months or so recovering because the mixture of chemo followed by that massive surgery and some complications absolutely knocked me for six.

I went through bouts of what I definitely call depression now, but back then, I never really saw anyone for my mental health. I always brushed that under the carpet. I now know a lot more about the significance of something like depression, anxiety, or mental illness, but back then I almost used it as an excuse because of what I was going through. I told myself it was completely normal, that I was feeling like this because I've been through that, and that was my justification for not seeking help or talking about it.

I was in my fifth year of being in complete remission, and a lot of cancer survivors strive towards that five-year mark. I got to a stage where I was almost 100% fit and healthy and was medically upgraded to the Army, which meant I could go on deployment. I got promoted to a captain and everything was looking fantastic.

My bowel started playing up a bit, but I've always had inconsistencies with my bowel —- ulcerative colitis, IBS — so I’ve been used to a bit of a dodgy gut. But in my head and my heart something didn't feel right, and I ended up going to the doctor and asking for a colonoscopy. I felt like I built up a fair bit of anxiety during those years, and if I got like a lump, or bump, or a rash, or enlarged lymph nodes in my neck, or whatever it might be, I'd always say to my partner, "Oh, what do you think this is?" So, naturally, I almost became a bit of a hypochondriac, which probably saved my life.

That's when I got told that I had bowel cancer, which was completely unrelated to the testicular cancer. It wasn't a relapse or testicular cancer spread, or anything like that. You just couldn't make the timing up — you get the all-clear for that five-year remission, and then as little as two, three months later, you're being told you've got another cancer. That was difficult.

I got the call from the receptionist, and my stomach sank when she said, "the doctor needs to see you this afternoon to go through the results." That's when I knew it was serious because he's not going to want to see me that afternoon if it was a bit of inflammation.

I went to the appointment with my partner. He didn't beat around the bush. After what I'd already gone through, being a bit older, a bit more mature, understanding the significance of it, that's when it really, really hit me because I felt like I was so vulnerable at that point in time. I remember leaving the rooms and just bursting into tears. Telling my family was difficult, to hear their voice and to put them through that level of pain again, I felt guilty that they'd be more upset, and so that was definitely one of the worst things I've had to do.

I often say I've got no doubt that testicular cancer saved my life, and what I mean by that is if I never had testicular cancer and still got bowel cancer down the track, there is no way I would've gone to a doctor and been as proactive with my health. The silver lining is that early detection absolutely saved my life. Bowel cancer's the second biggest cancer killer behind lung cancer, but it's also highly curable if you get it early. I had my entire large bowel and rectum removed, a process that’s come with plenty of challenges. When your large bowel, rectum and big chunks of your internal organs are removed, you can’t ever go back to normal. I go to the bathroom upwards of 12 times a day, I’m on medications for the rest of my life, get up during the night a few times, and it's been almost a year since I got rid of my ileostomy bag, the external bag that I had for eight months which is where part of your small bowel sticks out of your stomach and goes into a bag. When I’d eat and go to the bathroom, instead of sitting on the toilet, it goes into the bag, then you have to empty that bag throughout the day and change it every couple of days.

Now things are looking pretty good and I’m continuing to adapt and adjust to my current bowel set up without the ileostomy bag. Some days are worse than others, but that's life — we all have ups and downs. I’m also an advocate for keeping conversations about health going and for me, that's almost healing in itself because it makes it seem worthwhile.

My organisation, 25 Stay Alive, stemmed from my experiences. When I started sharing my story, I realised that yes, I was unique because of the two different cancers I'd gone through, but I wasn't unique in that there are so many other young men and women impacted by cancer in their 20s. I suppose it frustrated me that there didn't seem like there was much awareness about it.

Whether it’s others online or my closest mates, I'm a massive advocate of talking about these things. Everyday conversations can help, it doesn't need to be long-winded posts and podcasts or whatever, just simple conversations at the lowest level with old schoolmates you've known for 15 years or so.

I want people to build up a good relationship with a doctor, someone who they can trust. It's a good feeling when you walk out of doctor's appointment knowing you’re healthy. And if there is something wrong, you’ll hopefully get on top of it early because that's essentially what saved my life.

It does frustrate me when people say “oh I'm going to be 80 bucks out of pocket”, but you would happily, without hesitation, spend 80 bucks at the pub. People get reluctant to spend that on their health.

It's that old-school thinking of “she'll be right, I'm tough. I'm a bloke. I'm an Aussie guy. I don't need to talk about my emotions. don't need to book into a doctor.” That’s the mindset we have to change.

We don't want to build emotionally fragile kids, it's just a matter of making them aware of their health, plain and simple, because without your health, everything else is irrelevant. I guarantee your mindset changes very, very quickly when someone close to you, or God forbid, you yourself, go through something serious. They say, "Okay, that's maybe why I shouldn't have been putting it off." Early detection saved my life. Don't wait until it's too late.